So the seesaw remains level.

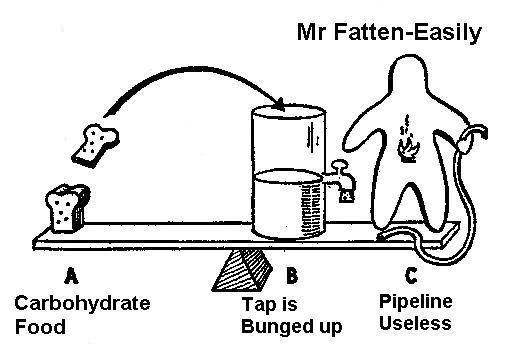

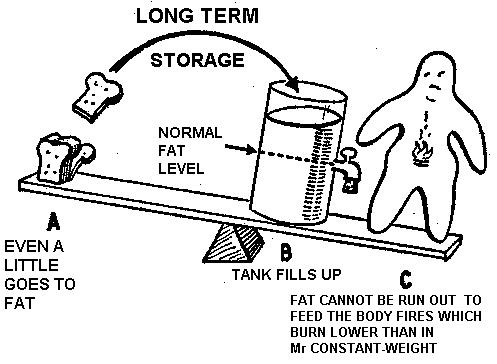

In Mr Fatten-Easily the picture is different:

Mr Fatten-Easily wants someone to come and take the cork out and fit back his pipeline from fat to fire, not someone to tell him to eat less.

So far, very little has been said about the dangers and disadvantages of being over-weight. This is because very little needs to be said that a fat person does not know only too well already.

Shakespeare in Two Gentlemen of Verona has written something which strikes to the heart of every sufferer from obesity:

"Not an eye that sees you but is a physician to comment on your malady."

Not a nice thought either, but uncomfortably true.

At the risk of depressing the over-weight reader, a few figures on longevity and the incidence of disease in relation to obesity will now be given. With the means of slimming effectively and painlessly already in his hand, it is perhaps legitimate to present facts which may scare him into doing something about getting his weight down. Mr. McNeill Love, surgeon to the Royal Northern Hospital in London and co-author of that "Bible" of surgery known affectionately to generations of medical students as Bailey and Love, wrote in a recent paper on the surgical hazards of obesity:

"A well-known insurance society states that a person fifty years of age who is 50 lb. over-weight, has reduced his expectation of life by 50%. Increased risks are also reflected in the mortality and morbidity of the obese when surgical procedures are required."

Fat people tend to forget that not only do they run an increased risk of dying early or developing diseases which interest the physician like hypertension, diabetes, arthritis and coronary thrombosis, but also that if they should ever have to have an operation they will make the surgeon swear as he struggles to distinguish the relevant anatomical landmarks in a sea of adipose tissue.

And even when the surgeon has managed to find the appendix or repair the hernia, the fat man's post-operative progress is bound to be poor compared with his lean brother's.

Next, a physician's view. Dr. John S. Richardson, consultant physician to St. Thomas's Hospital, writing in the Post-graduate Medical Journal, December, 1952:

"Insurance statistics show that between the ages of 45 and 50 for every 10 lb. over-weight there is roughly a 10% increase in the death-rate over the average for that age. This is largely a result of cardiovascular and renal disease. (Diseases of heart blood-vessels and kidneys.)"

Lastly, life insurance examination, the most ruthless estimate of our chances.

The late Dr. A. Hope Gosse, TD, MD, FRCP, consulting physician to St. Mary's and the Brompton Hospital, writing on obesity from the point of view of the insurance medical officer in the same number of the Post-graduate Medical Journal:

"Both for life assurance and sickness assurance the two commonest causes of 'loading' the premium are to be found in the figures for the weight or blood pressure of the proposer, when such figures are regarded as above the average for his height and age."

These are some of the dangers of obesity and it is clear that they increase as the weight goes up beyond what it should be for height and build.

Luckily the converse is also true. As a fat person's weight comes down so his chances of developing those diseases known to be associated with obesity become less and his expectation of life increases. This was strikingly demonstrated by Dr. Alfred Pennington when he slimmed the executives of E.I. du Pont de Nemours, the American chemical firm, on an unrestricted calorie, high-fat, high-protein diet similar to the one advocated in this book.

Shortly after the last war, the Medical Division of du Pont became concerned about the obesity of some of the staff and gave Dr. Pennington the job of finding out why orthodox low-calorie diets were so conspicuously unsuccessful in dealing with the problem. After an enormous amount of sifting through the scientific literature on the subject, Pennington came to the conclusion that Banting was right and that obesity is caused not by over eating but by an inability to utilise carbohydrate for anything except making fat.

He decided to by-pass this block in the pathway from starch and sugar to energy by withholding these foods, and gave fat and protein instead, in the proportion of one to three by weight (Stefansson's proportion on his year's all-meat diet).

The results amply justified all the ground work he had put in.

Here is part of a report of an interview he gave to Elizabeth Woody, published in a supplement to Holiday Magazine:

"Of the twenty men and women taking part in the test, all lost weight on a dietary in which the total calorie intake was unrestricted. The basic diet totalled about 3,000 calories per day, but meat and fat in any desired amount were allowed those who wanted to eat still more. The dieters reported that they felt well, enjoyed their meals and were never hungry between meals. Many said they felt more energetic than usual; none complained of fatigue. Those who had high blood pressure to begin with were happy to be told by the doctors that a drop in blood pressure paralleled their drop in weight.

The twenty 'obese individuals,' as the paper unflatteringly terms them, lost an average of twenty-two pounds each, in an average time of three and a half months. The range of weight loss was from nine to FIFTY-FOUR POUNDS and the range of time was from about one and a half to six months.

Now let's take a look at the effects the regimen had on some of the people in this group who suffered from high blood pressure.

Dr. Pennington sorted out from the papers strewn over his desk half a dozen sheets of graph paper filled with lines and notations. A solid line stood for the patient's weight on a given date, while a dotted line recorded his blood pressure at that time. The two lines told a thrilling and unmistakable story. As they passed vertical divisions representings weeks and months, the dotted lines dipped almost precisely parallel to each dip in the solid lines. Certainly, as Dr. Gehrmann (Dr. George H. Gehrmann, Medical Director of du Pont's Medical Division) had suggested earlier, over-weight and high blood pressure seemed to be Siamese twins. Most gratifyingly, on each sheet both lines progressed as a beautiful slant from the upper left quadrant of the sheet to a point near the lower right-hand corner."

With regard to the discomforts and disadvantages of obesity, it is appropriate to return to William Banting, whose work has had to wait a hundred years for proper recognition.

When his Letter on Corpulence was published, medical men called his system a humbug and held it up to ridicule. In those days of aggressive drugging and violent purgation this was to be expected.

On 28th December, 1956, the B.B.C. gave Banting the credit he and his medical adviser, William Harvey, have long deserved.

In a broadcast called "Beautifully Less" devised by Nesta Pain, about the best scientific scriptwriter working to-day, with advice from Professor Sir Charles Dodds and Dr. Alexander Kennedy, Banting's system of weight reduction was dealt with at length and described as "thoroughly sound."

Let him speak for himself in his delightful nineteenth-century English:

"Oh! that the faculty would look deeper into and make themselves better acquainted with the crying evil of obesity-that dreadful tormenting parasite on health and comfort. Their fellow-men might not descend into early premature graves, as I believe many do, from what is termed apoplexy, and certainly would not, during their sojourn on earth, endure so much bodily and consequently mental infirmity.

Corpulence, though giving no actual pain, as it appears to me, must naturally press with undue violence upon the bodily viscera, driving one part upon another, and stopping the free action of all. I am sure it did in my particular case, and the result of my experience is briefly as follows:

I have not felt so well as now for the last twenty years.

Have suffered no inconvenience whatever in the probational remedy.

Am reduced many inches in bulk, and 35 lb. in weight in thirty-eight weeks.

Come down stairs forward naturally, with perfect ease.

Go up stairs and take ordinary exercise freely, without the slightest inconvenience.

Can perform every necessary office for myself.

The umbilical rupture is greatly ameliorated, and gives me no anxiety.

My sight is restored-my hearing improved.

My other bodily ailments are ameliorated; indeed, almost passed into matter of history."

It is still unfortunately true that many doctors do not understand obesity for what it is: an error of metabolism, an internal defect, affecting some people and not others, quite apart from the actual amount of food consumed.

The standard medical approach to obesity in this country is still to give the patient a low-calorie diet sheet, with or without some pills to depress appetite, and to leave him to try and starve the fat off. Banting received the same kind of treatment (without the pills) from most of the doctors he consulted. And The Times Medical Correspondent to-day still writes this sort of stuff.

"The problem of slimming boils down to the quite simple one of reducing the amount of food eaten. . . . If you are putting on weight, you are consuming more energy in the form of food than you are expending in the form of physical exertion."

No suggestion here that excessive fat storage might be independent either of the food intake or the energy expenditure or both. Nor any mention of the possibility that different kinds of food might be metabolised differently in fat and in thin people.

Yet as long ago as 1898, Zuntz in Berlin reported a case of a man who gained weight on a high-carbohydrate diet and lost weight on a high-fat diet of equal caloric value.

In 1907, Benedict and Milner in the United States confirmed this observation with a subject who did a uniform amount of work each day on a bicycle ergometer, and since then the lowered metabolism of the obese, particularly on calorie-restricted diets, has been confirmed again and again during energy balance studies.

It is well known that Donaldson and Pennington in America have been slimming people on high-fat "Eat-as-much-as-you-like" diets since 1944, and since 1950 such diets have been finding their way into women's magazines in the U.S.A.

But in this country, the writers of popular books on slimming still say this kind of thing:

"During an absolute fast, a person naturally lives on the deposits (that is fat and carbohydrate reserves) which we have within us-first and foremost in the liver. It has been found that we use up the carbohydrate reserves first. There are some ¾-1 lb. of them. After that comes the turn of the fat, which we are so anxious to get rid of.

This fact has, indeed, given rise to an extraordinary slimming cure, which for a brief period had a certain success. The patient was given fat! Meanwhile the body used up its carbohydrate reserves. But over twice as much sugar is needed to give the same amount of calories as fat-so the patient lost weight. He did so even more because the sugar (carbohydrate) reserve holds three times its weight of water, which is also eliminated when the sugar is burnt up. The fat which was taken instead held a smaller quantity. Thus the patient lost weight, but at the same time became fatter-and it is fat which we find it difficult to get rid of.

Therefore that cure's success did not last long."

This passage, which I find confusing, is from Eat, Drink and be Slim, by Edward Clausen and Knud Lundberg, revised and adapted in 1955 by Miss G. H. Donald of the Good Housekeeping Institute .

These two writers go on to pour scorn on the idea that obesity may be the result of altered metabolism:

"Let the truth be told," they write. "This is not the reason we have become fat. It is because we like food. Our whole trouble is that we eat more than we use up — and the balance is stored in the form of a corporation . . . the truth about metabolism is that 95% to 98% of all sufferers from fat have a normal base metabolic rate. . . . Our trouble lies not in how food changes inside us, but in what food we eat.

Glausen and Lundberg have got it the wrong way round. To borrow their form of words: The truth about the basal metabolic rate (expressed per pound of body weight) of people who are gaining weight is that in 95% of cases it is substantially lower than normal. Their trouble lies in how food changes inside them, not in how much they eat.

Dr. Pennington has put the matter straight once and for all in the summary to his excellent paper "Obesity: Over-nutrition or Disease of Metabolism?" published in 1953 in the American Journal of Digestive Diseases:

"Analysis of the results, of studies of the energy exchange in obesity, in regard to their evidence for or against a passive dependence of the excessive energy stores on the balance between the inflow and the outflow of energy, indicates that these stores have a significant degree of independence of the energy balance. This appears to necessitate an explanation of obesity on the basis of some intrinsic metabolic defect. The decline in energy expenditure which occurs when the obese go on low calorie diets appears to have the same significance as it has when people of normal weight are subjected to under-nutrition. A treatment of obesity, alternate to that of caloric restriction, takes into account the metabolic defect in obesity, aims at a primary decrease in the excessive energy stores, and allows for weight reduction without any decline in the energy expenditure and without any enforcement of caloric restriction."

This theory is the only one which explains all the known facts about obesity and for ten years it has stood up to the only valid test of any theory-practical application. Nobody can now deny that most fat people can grow slim on high-fat, high-protein diets and still eat as much as they like.

Leaving aside Beddoes in 1793 and Harvey in 1856, who had ideas a bit before their time, ever since 1907, when Von Noorden in America suggested a defect in the metabolism of carbohydrate in the obese (and compared it, as Harvey did, to the diabetic's inability to metabolise sugar), the abnormal metabolism of fat people during weight gain and on low-calorie diets has been hinted at in paper after paper in the medical and scientific journals.

Even if all the early investigators did not agree on the interpretation of their results, for the past fifteen years at least, the evidence for Mr. Fatten-Easily's defective metabolism of carbohydrate has been overwhelming.

A simple equation makes it easier to understand the point:

| energy intake | = | energy storage | + | energy expenditure |

| calories in as food | = | calories put away as fat | + | calories used up for energy |

| A | = | B | + | C |

|---|

If B changes passively with variations in A and C, then the fat depots are just storage dumps to be depleted or filled up according to differences between the food intake (A) and the energy expenditure (C).

This is what all the "cut-down-the-calories" experts have believed since the time of William Wadd and the Prince Regent. But if, as I believe to be the case, the fatty tissues of the body are not inert but highly active and concerned particularly with the metabolism of carbohydrate, then in obesity, B might vary independently of A and C under conditions of disturbed or abnormal metabolism.

Weight would then be gained on quite a small intake of carbohydrate food because most of it was being diverted into storage and prevented from being got out again for use.

This is what seems to happen in the obese and a possible cause is the pyruvic acid or some such block on the normal metabolic pathway from carbohydrate to energy and from stored fat to energy.

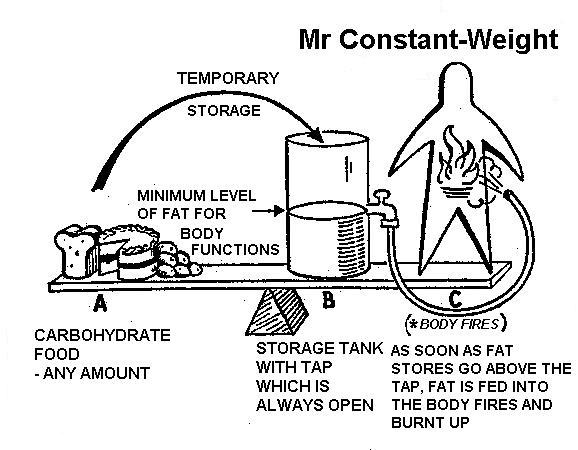

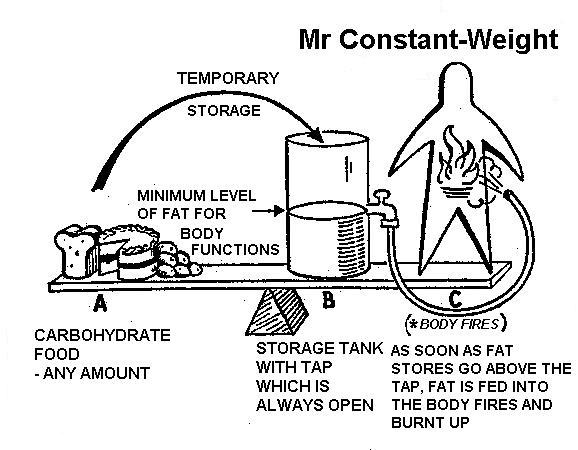

It is now thought probable that Mr. Fatten-Easily's inability to burn up carbohydrate and his tendency to make and store excessive fat may be due to lack of a hormone: a fat-mobilising factor. Lack of this hormone may be preventing him from using the carbohydrate he eats for anything except making stored fat. Expressed pictorially, the energy balance looks like this for Mr. Constant-Weight eating carbohydrate:

So the seesaw remains level.

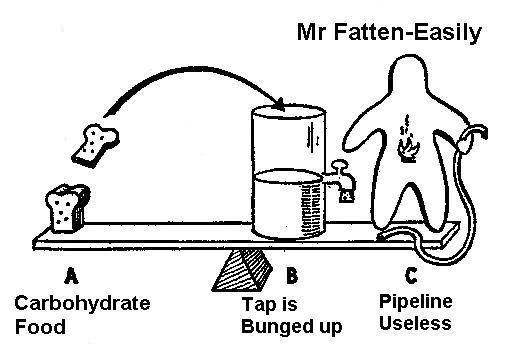

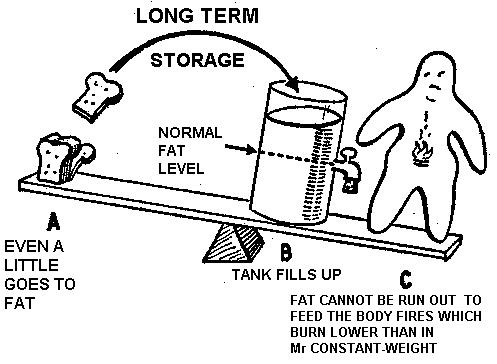

In Mr Fatten-Easily the picture is different:

Mr Fatten-Easily wants someone to come and take the cork out and fit back his pipeline from fat to fire, not someone to tell him to eat less.

It may be a long time before the hormone which will take the cork out and enable Mr. Fatten-Easily to utilise carbohydrate fully is available for general use in the treatment of obesity, but we now have the next best thing: an understanding of the fat person's defective capacity for dealing with carbohydrate and a dietary means of correcting it WITHOUT RESTRICTING THE AMOUNT OF FOOD EATEN.

Eat-Fat-and-Grow-Slim is not only a practical proposition but it is good for a fat person and will make him feel well while it gets his weight back to normal.

Another great advantage of the diet is that it will not take your weight below normal for your height and build, nor will it do you any harm if you only want to lose a few pounds.

But if this is the case, it will not be necessary to restrict carbohydrate to the minimum, but merely to cut it down to a level where the amount of pyruvic acid (which is preventing you mobilising your fat) in your body is reduced to a level at which you can lose weight. This level can be found by trial and error. As Dr. Pennington puts it:

"It seems that the emphasis should be put on fat as a major source of energy, with carbohydrate restricted to the degree necessitated by the obesity defect, and ample protein allowed for its well-recognised benefits to health."

There are only three classes of people who should not go on the diet:

Hypoglycaemia manifests itself gradually, with symptoms like sweating, flushing or pallor, numbness, chilliness, hunger, trembling, weakness, funny feelings in the head, raised pulse, palpitations, apprehension and fainting.

Such people should be forewarned that if any of these symptoms do develop on the diet, it means they should increase their carbohydrate. A sweet, syrupy drink will relieve the symptoms in 20 minutes.

Children should not be put on this diet without personal medical advice, but in my experience there is no danger in their following it. I have slimmed a number of fat children from ages between 9 and 17 with success on this regime.

Results come quickly-more quickly than in adults. But with children and adults I now insist that fats be eaten as fresh as possible and unprocessed. Fat-soluble vitamins and other substances in fat which are essential to growth and health, come better from natural sources.

It is worth stressing again that none of Professor Kekwick's obese patients developed low blood sugar on high-fat diets so that hypoglycaemia is not a serious hazard for a fat person.

Any doctor who has seen a fat patient struggling in semi-starvation to keep to a low-calorie diet and do a day's work must have wished for a better way of helping his patient.

A high-fat, high-protein, low-carbohydrate unrestricted calorie diet is that better way.

Many doctors are sceptical, and rightly so, of books on medical subjects written for the public, as this is.

Yet even the most sceptical would be convinced if they could have seen fat patients in Professor Kekwick's wards at the Middlesex Hospital, losing only a pound or two on a 1,000-calorie diet containing a high proportion of carbohydrate, being switched to a high-fat diet with a much greater calorie intake and immediately losing weight, then ceasing to lose again when put back on a high-carbohydrate calorie-restricted diet.

Starch and sugar are the culprits. Cut them right down and eat fat and protein in the palatable proportion of one to three. You will then grow slim while you eat as much as you like and feel well because you will be eating the best kind of food. It is as simple as that.

Never mind the theory, which may still have to be modified as research goes on. Try out the diet. It works.